LockBit 3.0’s Bungled Comeback Highlights the Undying Risk of Torrent-Based Data Leakage

Cyber Threat Intelligence

In late February, the beleaguered LockBit 3.0 ransomware group threatened

to release court documents related to former U.S. President Donald Trump, which were compromised in the January 29 hack of Fulton County in Georgia, unless the county paid a ransom by March 2. Notably, this threat immediately proceeded Operation Cronos, a major international law enforcement takedown that dismantled and vandalized LockBit 3.0’s online infrastructure and victim-shaming website on February 20.

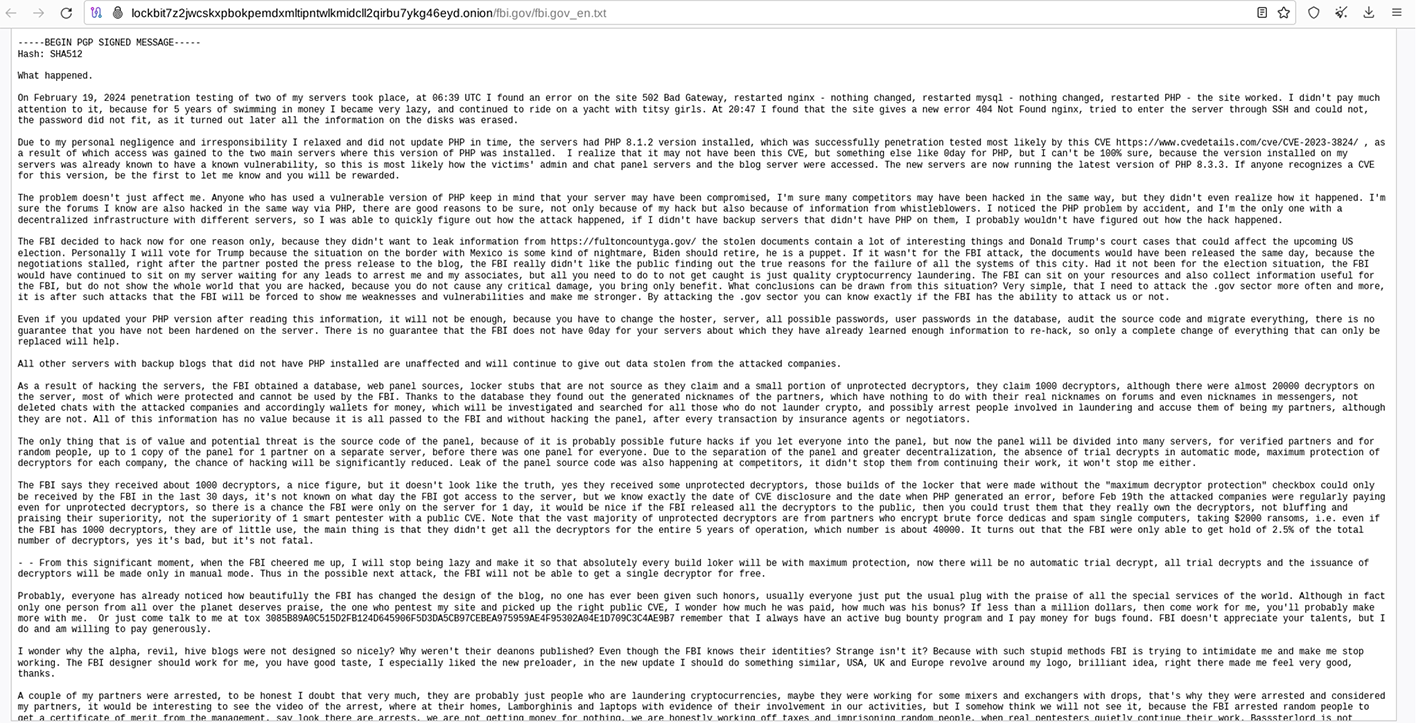

LockBit 3.0 quickly moved to restore their data leak site (DLS) and posted a long “rambling” statement in response to the takedown. The group alleges that law enforcement compromised their previous Dark Web DLS by exploiting a vulnerability in the PHP programming language, a common tool for website development. But the ransomware gang appears to have been making false claims regarding their post-Cronos possession of sensitive Fulton County Court data. As for the other victims LockBit 3.0 listed on their restored DLS, data associated with those postings appears to be recycled files from previous breaches. LockBit 3.0 ultimately adjusted the Fulton County ransom-payment deadline to February 29 and removed the listing from their DLS the same day, claiming the county had paid.

However, Fulton County officials denied ever paying a ransom. Beyond the reputational damage LockBit inflicted on its own organization with their presumed bluff about their resurgence and other empty threats, the group’s leadership has recently been besieged by claims of fraud and breach of contract by their affiliates. Specifically, the group’s infamous leader LockBitSupp has recently been banned from two high-authority Dark Web forums, XSS and Exploit, and is facing similar allegations of scamming affiliates on RAMP, their last remaining cybercrime-forum haven. While LockBitSupp battles to preserve their underground reputation and their ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) operation in general, law enforcement agencies investigating the LockBit 3.0 RaaS have noted that the gang maintains a broad network of affiliates.

Despite wide interest in the unfolding LockBit 3.0 comeback saga, this Resecurity report will cover a unique technical feature related to the gang’s operating model, namely LockBit 3.0’s use of Peer-to-Peer (P2P) platforms to disseminate data leaks through Torrent files. But before we dive into LockBit 3.0’s P2P data-sharing schemes and key audience segments believed to be accessing their torrent links, Resecurity will provide some recent background on the gang’s over-hyped “comeback.”

LockBitSupp’s Crisis-PR Bluster

In their rebuttal to the Cronos takedown, LockBitSupp remained in character and taunted the FBI, boasting: “The FBI states that my income is over 100 million dollars, this is true, I am very happy that I deleted chats with very large payouts, now I will delete more often and small payouts too. These numbers show that I am on the right track, that even if I make mistakes it doesn't stop me and I correct my mistakes and keep making money. This shows that no hack from the FBI can stop a business from thriving, because what doesn't kill me makes me stronger.”

LockBitSupp also claimed the court data acquired in the Fulton County ransomware breach had the potential to “affect the upcoming US election” – a move that likely constitutes the first time a high-profile ransomware actor has threatened a capability of this nature. Nevertheless, the boast appears to be completely false at this point, seeing as they no longer seem to have access to whatever Fulton County Court data their affiliates managed to seize.

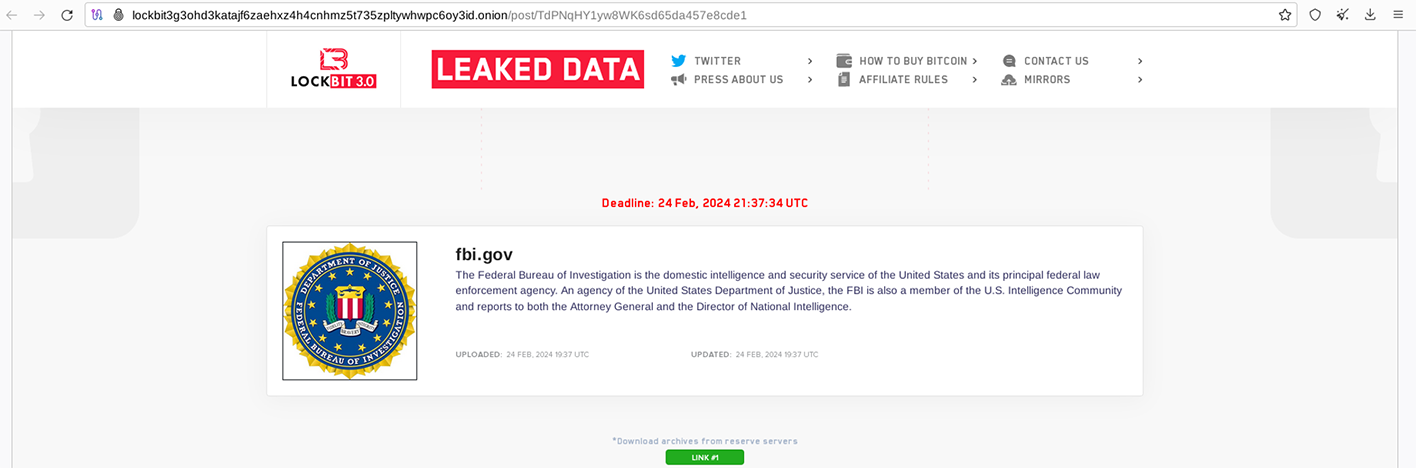

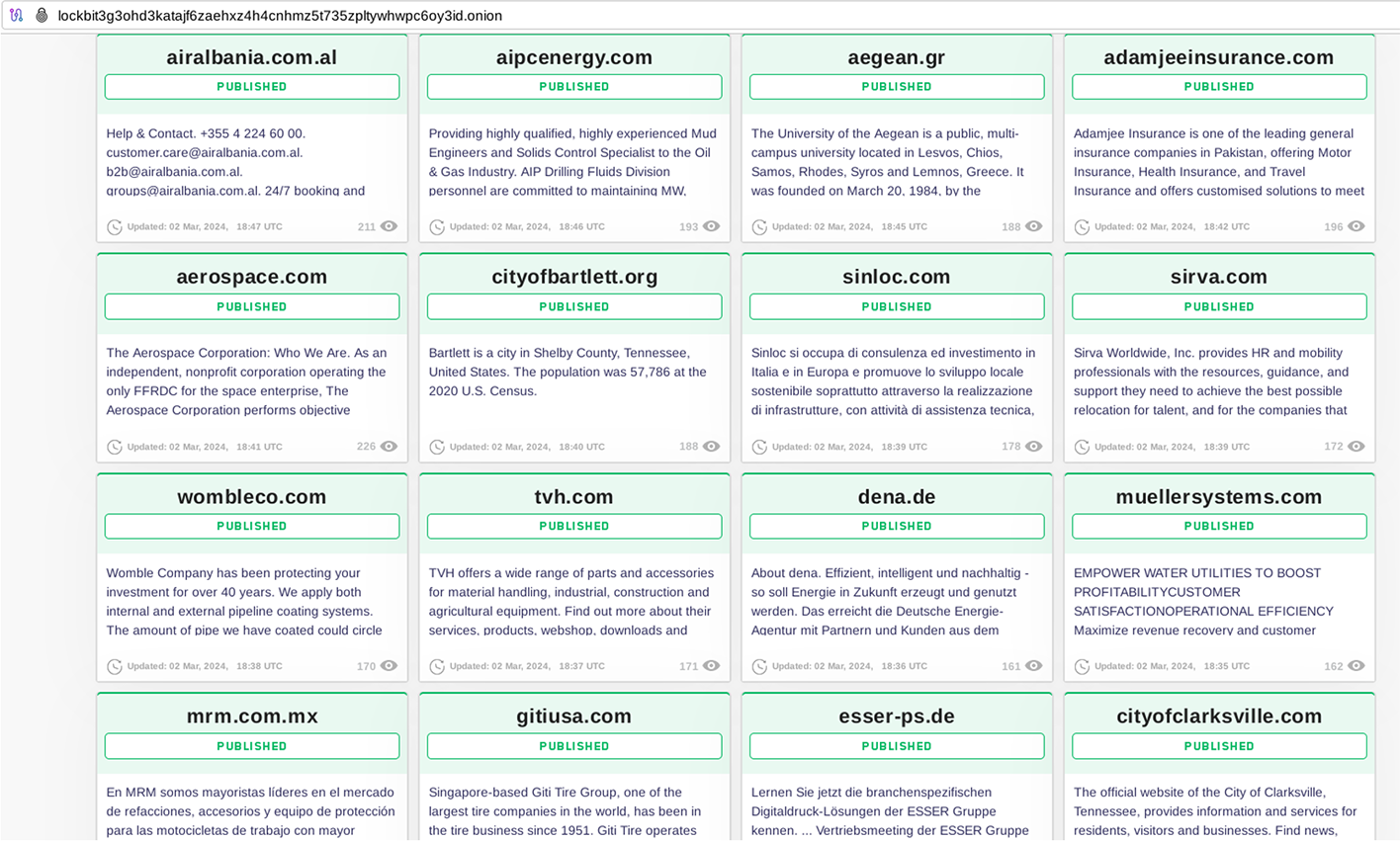

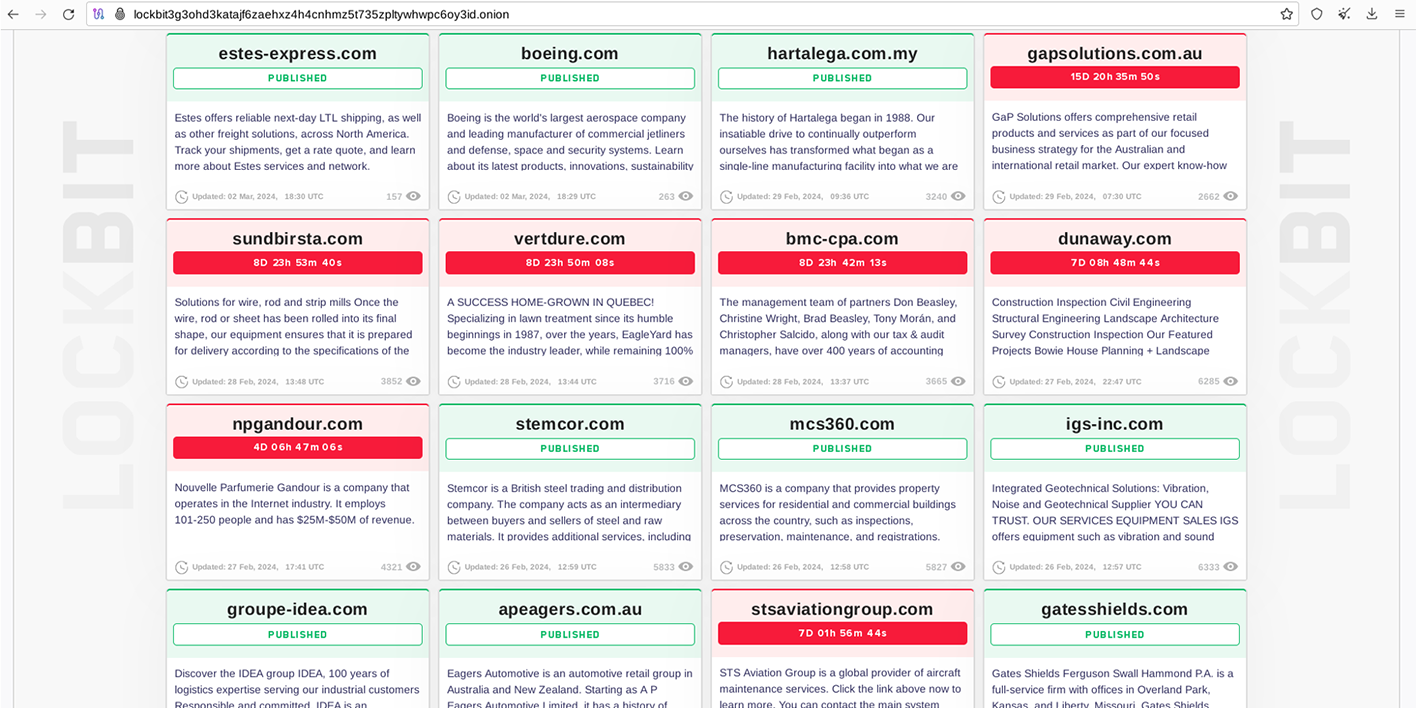

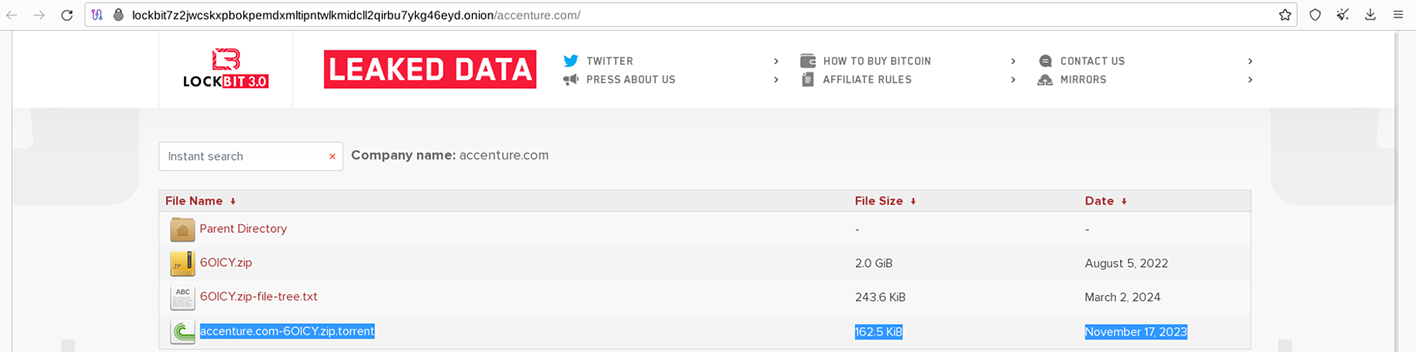

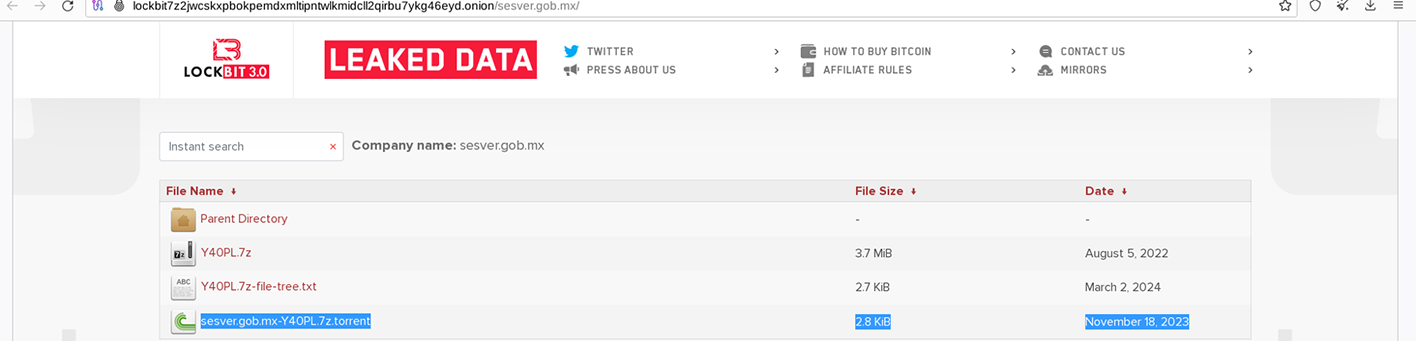

In addition to their published response to the FBI, LockBit 3.0 also established a new TOR DLS showcasing a limited number of purported victims and their corresponding stolen data. However, virtually all these victim data sets appear to have been backdated. At this point, the gang appears to be recycling old data leaks to generate hype about their resilience in the face of global law enforcement intervention. Below are some screenshots of LockBit 3.0’s purported victim listings from March 1 and March 2.

On March 2, 2024, Lockbit 3.0 claimed to publish new data leaks from various victims.

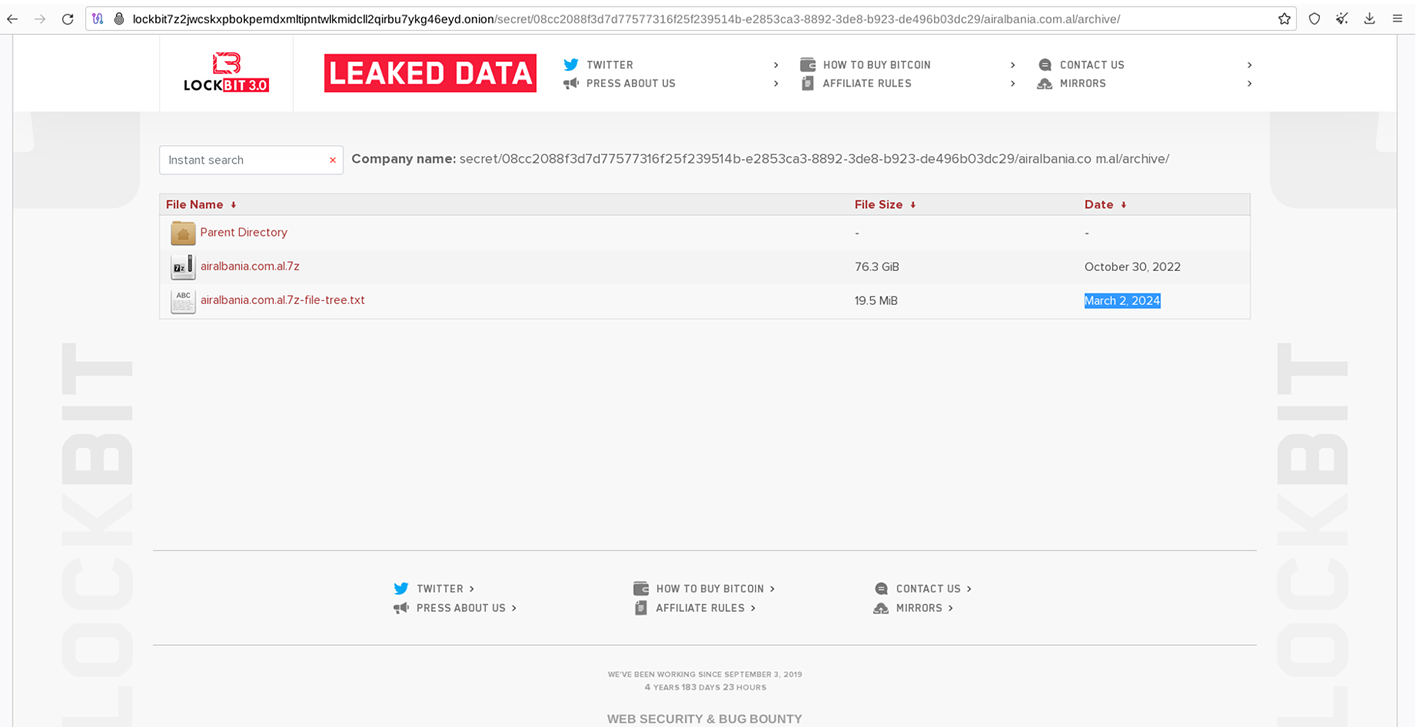

However, none of these victims saw any new information disclosed, except for additional file listings, as was the case with Air Albania:

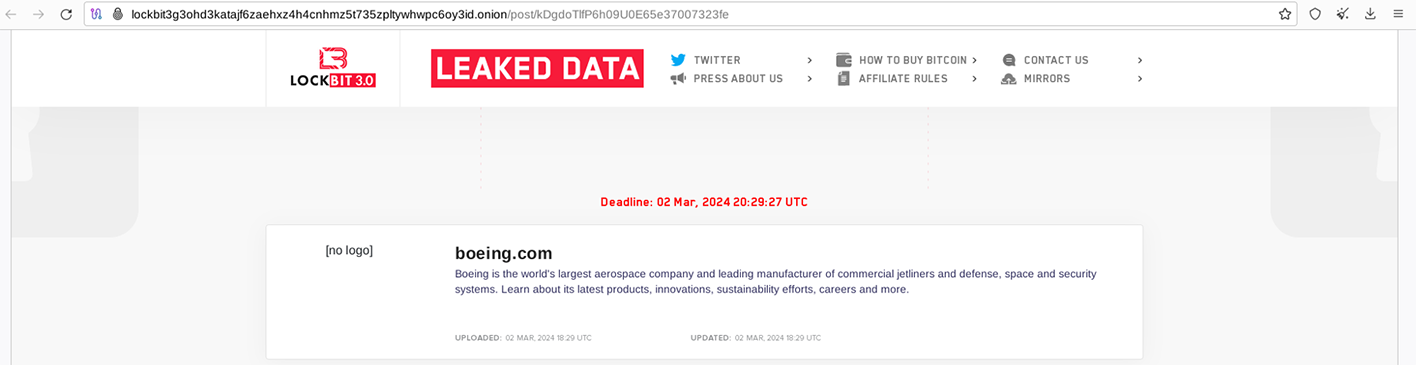

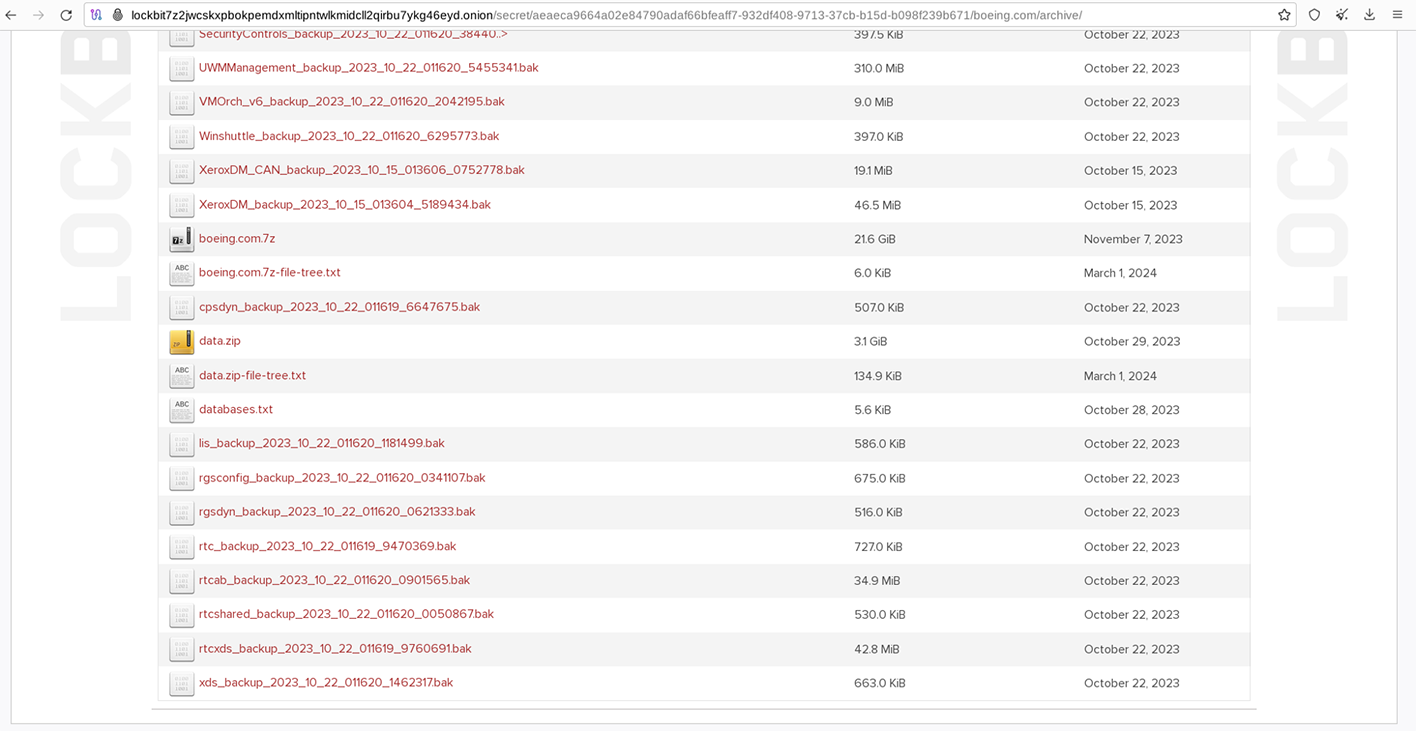

In some instances, victims like Boeing, which was slated for a March 2 publication, had actually been published months earlier.

In reality, Lockbit 3.0 had published Boeing data as far back as October 27, 2023, with the files themselves being dated October 22, 2023.

The recent update displayed this victim listing with a March 2 ransom deadline.

However, there were only two new files uploaded for the Boeing listing, with both additions dated March 1, 2024.

This pattern of backdating is also evident in many of LockBit’s previous leaks. As of now, the group has announced several new leaks with a projected ransom deadline/publication date of March 12. It remains uncertain whether these new leaks will actually materialize or if the data will be recycled from previous breaches. Nevertheless, the LockBit 3.0 gang want the world to believe that they remain active and operational.

P2P Communications and Torrents

More noteworthy than LockBit 3.0’s ongoing crisis-PR offensive is the group’s use of P2P platforms to disseminate data leaks via torrent files. Why is this tactic significant? Firstly, even if the group's infrastructure is partially disrupted, RaaS operators can make stolen data accessible to a wide audience via decentralized torrent networks. Once downloaded, users in possession of these files automatically begin seeding them, meaning they become peer nodes in sharing this data within the torrent network. People who download these torrent-based ransomware links effectively become active participants in the data leak, just like users sharing pirated movies or music.

Stopping this activity poses a significant challenge, like the difficulty the music, film, and TV industries face in combating content piracy through torrent trackers. Often overlooked is the fact that Lockbit 3.0 was one of the first ransomware groups to start incorporating leaked data into torrent files for download and uploading these archives to TOR.

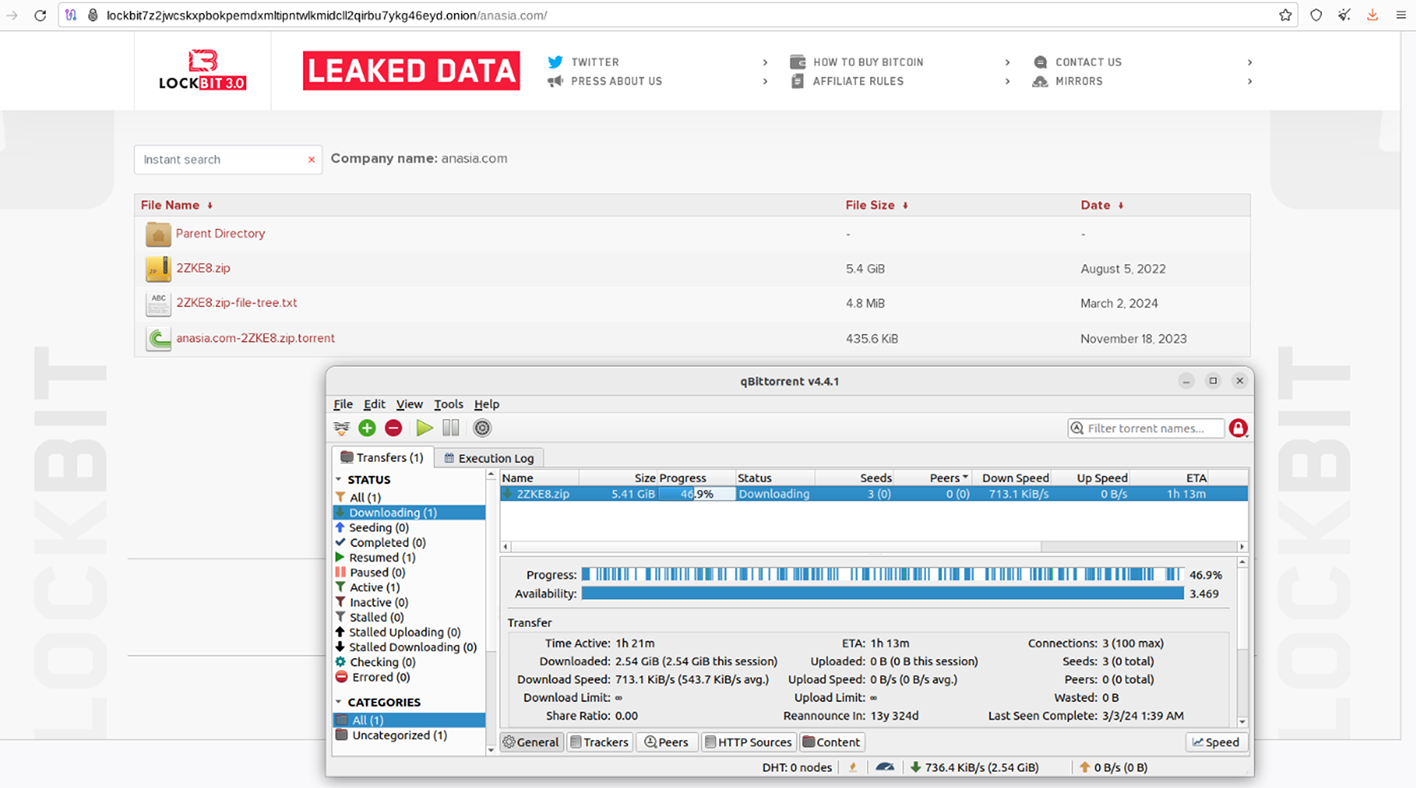

As of today, nearly 20 victim organizations listed on LockBit 3.0's Dark Web DLS are associated with torrent links. These victims encompass government organizations from Mexico, defense contractors, and leading law firms.

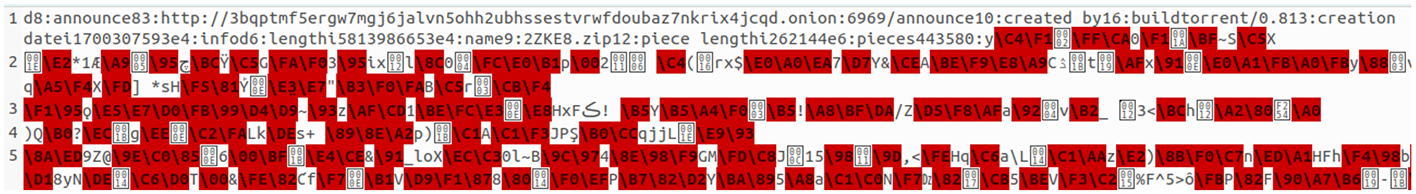

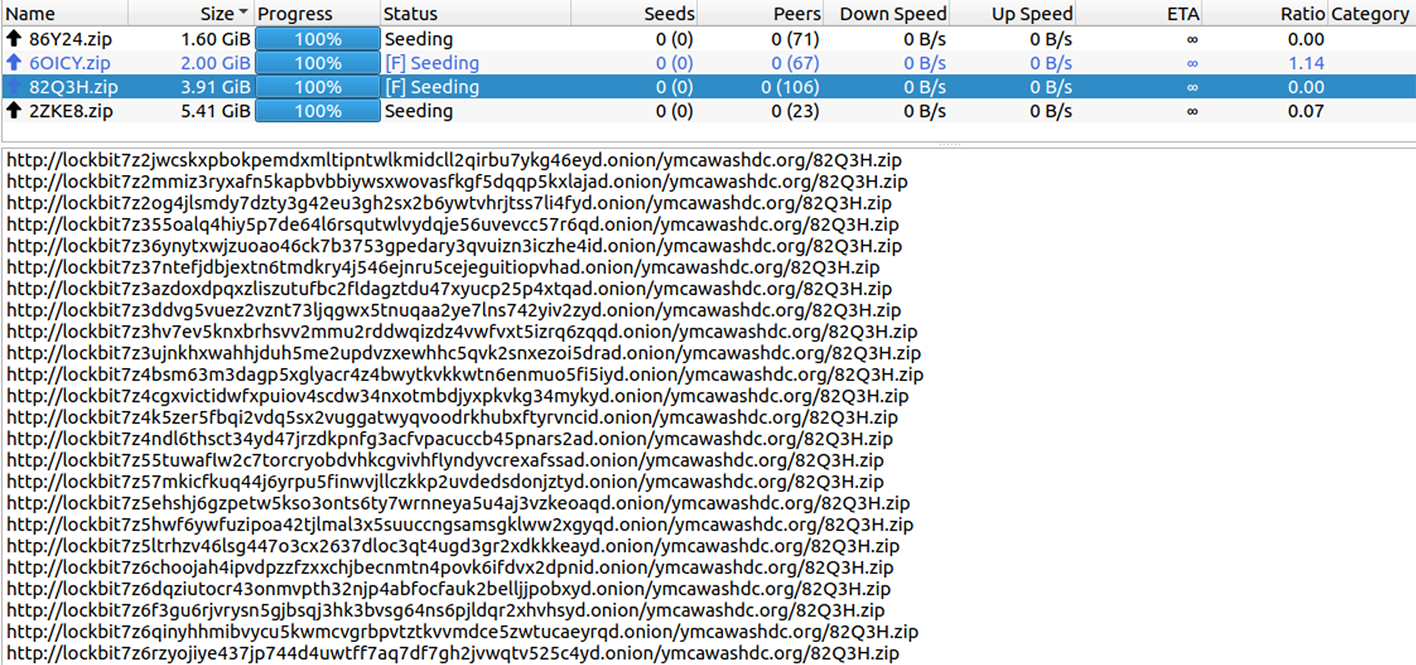

Resecurity has acquired all torrent files added before and after the March 2nd update, with the goal of analyzing P2P communications related to leaked data, in addition to TOR network connections.

Each of the torrent files we analyzed contained a link to a server with a hidden service on the TOR network, specifically indicating the sources for download:

http://3bqptmf5ergw7mgj6jalvn5ohh2ubhssestvrwfdoubaz7nkrix4jcqd.onion:6969/announce

We set up qBittorrent with TOR support (as SOCKS5) and observed that there were consistently three stable seeds available for nearly every torrent file shared by the group.

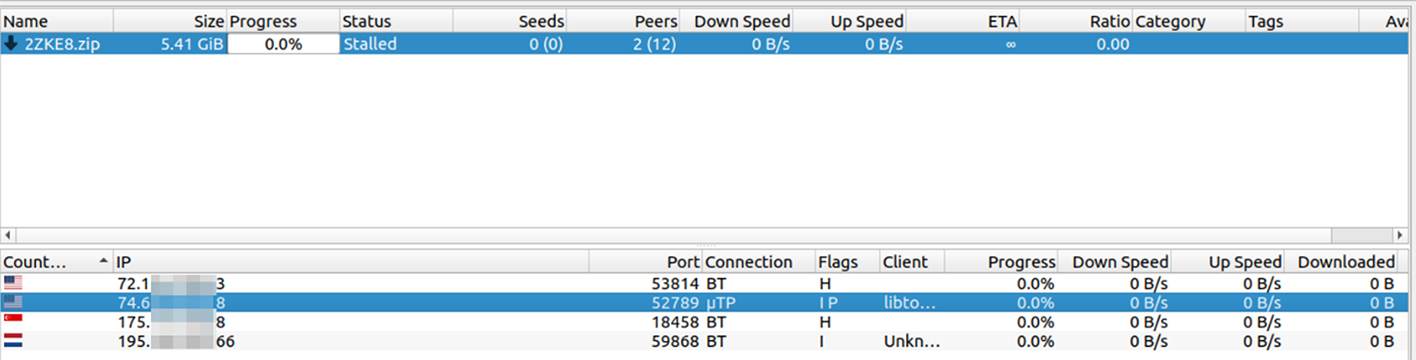

During this process, we logged a significant number of peers originating from various countries. In some cases, these peers used TOR as a relay.

Once Resecurity analysts downloaded these files, we became a LockBit torrent file-seeder. This enabled Resecurity to configure a stand to track LockBit-curious peer connections.

Following the announcement of the March 2nd leak, the number of LockBit-curious peers increased exponentially. This surge suggests a heightened interest from underground actors connected to Lockbit 3.0's activities, including their former affiliates, as well as data brokers eager to obtain stolen records. This group isn't limited to cybercriminals; it also encompasses industry competitors and corporate intelligence firms that are keen to opportunistically leverage the leaked data to their advantage.

Lockbit 3.0 is not the only group to have operationalized torrent file sharing. Other prominent RaaS groups that have employed this feature include Cl0P and Ransomed.VC, the latter of which we spotlighted last September for their attacks on major Japanese enterprises. At the time our Ransomed.VC report was published, this group was also distributing a torrent file that contained data from at least two victims. The gang used this torrent method as a primary delivery channel instead of TOR. Despite Ransomed.VC’s purported disbandment in November of last year, the torrents containing this stolen data remain accessible to people who have the download link.

Who Were the Peers?

Resecurity logged over 450 unique peers accessing leaked LockBit 3.0 data via torrents. Included in these logs were the torrent peers’ IP addresses and ports.

Notable hosts:

- the host with an IP address originating from China linked to extensive, malicious network activity

- the host with an IP address originating from Iran tied to one of the country’s scientific organizations

- the host with an IP address originating from subnet related to a business consulting firm

What Made These Deanonymizations Possible?

Accessing torrent links via TOR is widely recognized as a poor security practice. This concern was first flagged by security researchers nearly 15 years ago.

According to https://blog.torproject.org/bittorrent-over-tor-isnt-good-idea/:

There are three pieces to the attack (or three separate attacks that build on each other, if you prefer). The first attack is on people who configure their Bittorrent application to proxy their tracker traffic through Tor. These people are hoping to keep their IP address secret from somebody looking over the list of peers at the tracker. The problem is that several popular Bittorrent clients (the authors call out uTorrent in particular, and I think Vuze does it too) just ignore their socks proxy setting in this case. Choosing to ignore the proxy setting is understandable, since modern tracker designs use the UDP protocol for communication, and socks proxies such as Tor only support the TCP protocol -- so the developers of these applications had a choice between "make it work even when the user sets a proxy that can't be used" and "make it mysteriously fail and frustrate the user". The result is that the Bittorrent applications made a different security decision than some of their users expected, and now it's biting the users. The attack is actually worse than that: apparently in some cases uTorrent, BitSpirit, and libTorrent simply write your IP address directly into the information they send to the tracker and/or to other peers. Tor is doing its job: Tor is _anonymously_ sending your IP address to the tracker or peer. Nobody knows where you're sending your IP address from. But that probably isn't what you wanted your Bittorrent client to send. That was the first attack. The second attack builds on the first one to go after Bittorrent users that proxy the rest of their Bittorrent traffic over Tor also: it aims to let an attacking peer (as opposed to tracker) identify you. It turns out that the Bittorrent protocol, at least as implemented by these popular Bittorrent applications, picks a random port to listen on, and it tells that random port to the tracker as well as to each peer it interacts with. Because of the first attack above, the tracker learns both your real IP address and also the random port your client chose. So if your uTorrent client picks 50344 as its port, and then anonymously (via Tor) talks to some other peer, that other peer can go to the tracker, look for everybody who published to the tracker listing port 50344 (with high probability there's only one), and voila, the other peer learns your real IP address. As a bonus, if the Bittorrent peer communications aren't encrypted, the Tor exit relay you pick can also watch the traffic and do the attack. That's the second attack. Combined, they present a variety of reasons why running any Bittorrent traffic over Tor isn't going to get you the privacy that you might want. So what's the fix? There are two answers here. The first answer is "don't run Bittorrent over Tor". We've been saying for years not to run Bittorrent over Tor, because the Tor network can't handle the load; perhaps these attacks will convince more people to listen. The second answer is that if you want your Bittorrent client to actually provide privacy when using a proxy, you need to get the application and protocol developers to fix their applications and protocols. Tor can't keep you safe if your applications leak your identity. The third attack from their paper is where things get interesting. For efficiency, Tor puts multiple application streams over each circuit. This approach improves efficiency because we don't have to waste time and overhead making a new circuit for every tiny picture on the aol.com frontpage, and it improves anonymity because every time you build a new path through the Tor network, you increase the odds that one of the paths you've built is observable by an attacker. But the downside is that exit relays can build short snapshots of user profiles based on all the streams they see coming out of a given circuit. If one of those streams identifies the user, the exit relay knows that the rest of those streams belong to that user too. The result? If you're using Bittorrent over Tor, and you're _also_ browsing the web over Tor at the same time, then the above attacks allow an attacking exit relay to break the anonymity of some of your web traffic. |

That said, downloading data from torrent resources that involve the TOR network carries a substantial risk of deanonymization for end users. This applies equally to cybercriminals and other underground figures interested in Lockbit 3.0's data. Indirectly or directly, they may become targets of surveillance, making this access gateway highly inadvisable. However, for research purposes, this transparency can be advantageous. By analyzing peers interested in LockBit 3.0’s data, it’s possible to identify high-risk hosts accessing it and potentially glean valuable cyber-threat intelligence (CTI) insights.

Our approach is derived from the anti-piracy domain, particularly from the tactics technology companies in this space use to pinpoint IP addresses involved in the illegal sharing of copyright-protected intellectual property. A notable success story in this area was when two leading anti-piracy companies involved in the U.S. Copyright Alert System (CAS) scheme, BayTSP and Peer Media, monitored thousands of torrent files back in 2012. As reported by TorrentFreak, anti-piracy firms BayTSP and Peer Media significantly ramped up their activities, effectively surveilling the download habits of BitTorrent users to gather statistics and insights.

“As for the number of torrents that are being watched, over a period of a month BayTSP connected to 3,657 torrent files and Peer Media to 3,752 torrents. Although ScanEye tracks hundreds of thousands of torrents, these lists are not extensive,” reported TorrentFreak. For years companies such as BayTSP and Peer Media worked with movie studios and record labels to track the IP addresses of torrent file-downloaders, so violators could be reported to their Internet providers. Beyond two “educational” warning notices, CAS operated under a six-strike system where repeat violators faced an escalating set of punishments under the anti-piracy regime, including temporary Internet disconnects and legal action.

In fact, the Motion Picture Association (MPA) and the Recording Industry Association of America ( RIAA) used the collected data to sue egregious file-sharers. However, The CAS system was discontinued in 2017, as the entertainment industry has devised new methods of combatting online piracy.

Conclusion

The dilemma related to torrents and victim data leaked by LockBit 3.0 persists even after the Cronos disruption. The main challenge is deterring actors who have already downloaded the data from seeding it. This task is complex, particularly when it comes to deterring actors operating in politically adversarial jurisdictions or where the rule of law is weak. These countries could become "safe havens" for establishing enduring cybercriminal torrent trackers, potentially replacing or at least supplementing the TOR network. Beyond the Dark Web, Data Leak Sites might evolve into Data Leak Torrents, offering enhanced privacy and accessibility, thereby facilitating the distribution of stolen data. This scenario presents a novel challenge for the information-security industry that requires advanced preparation and planning. Thanks to LockBit 3.0 and their “intrepid” leader, Resecurity has laid the initial groundwork for confronting this emerging threat.